A Los Angeles dream of turning 4th Street into a bike-friendly thoroughfare.

If you've driven through Los Angeles in recent months, there's a good chance that you've seen some unusual bike signage. Black and white posters with a bike lane icon and the phrase “Caution! Please Pass With Care” (or sometimes "Precaución! Por Favor Pase con Cuidado”) have been springing up all over the city, wheat-pasted to electrical boxes and other roadside furniture. In the span of a few weeks, these signs have become near ubiquitous in certain parts of the city. Where did they come come from and who put them there? Reports on the signs origin may be somewhat mysterious, but one thing seems clear: They are part of a growing trend of DIY bicycle signage.

In previous installments of this column I have discussed some of the issues that need to be taken into account when it comes to bicycle route planning. The unfortunate reality of the planning process, however, is that it tends to be a long slow slog. Politics, budgets, and liability concerns can all serve to impede progress on what often seem, to the average cyclist at least, to be easy no-brainer solutions to bicycle infrastructure problems.

In Los Angeles, and around the country, there are a growing number of cyclists who, fed up with the slow progress of official development, have taken it upon themselves to start implementing DIY guerilla bike route infrastructure. These responses range from the purely practical to the whimsical and symbolic. All share the idea that if government is not going to look out for the interests of cyclists, cyclists will have to take matters into their own hands.

Los Angeles has seen a number of these guerrilla responses in recent years. DIY versions of signs from my proposed Better Bikeways signage system made brief appearances along L.A.'s 4th Street Bikeway in 2008, spending a few months warning motorists about the presence of bicyclists at major intersections before eventually being removed by the city. That same year a group calling itself the Department of DIY, gained attention by painting a guerrilla bike lane along a bridge spanning the Los Angeles river. It didn't take long for the city to take action and paint over the ersatz bike lane, but the move certainly drew attention to the need for additional miles of bike lanes in the city and helped to spur discussion on the subject of bike infrastructure development.

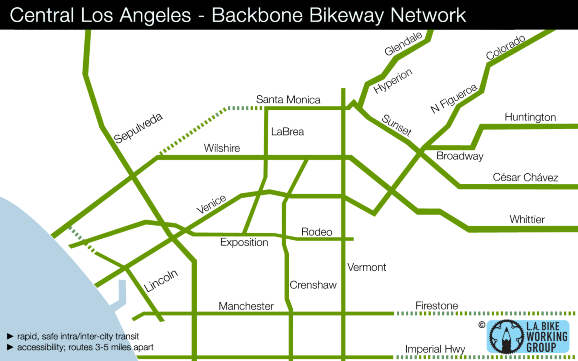

Other projects, while still maintaining a DIY approach, seek to exert a more direct influence on the official infrastructure planning process. The Backbone Bikeway Network, a project of the LA Bike Working Group, is one such undertaking. The Backbone network can be seen as a response to the mish-mash hodge-podge of infrastructure laid out by by the city in its latest proposed bike plan. The Backbone network aims to be something like a freeway system for bikes, laying out a system of major arterial routes that can get bikers from one side of the city to another. With this proposal the Bike Working Group hopes to influence the direction of the city's future bike route development, a "grass-routes" approach to urban planning.

A second type of project takes a more personal approach to infrastructure. Light Lane is a proposed product that uses bike-mounted high visibility DPSS Lasers to project a virtual bike lane on to the pavement behind the cyclist. This project gives cyclists the freedom to carry their bike lane with them wherever they travel.

Another proposal titled Contrail makes use of a simple chalk marking device to allow cyclists to leave a temporary physical trail documenting their route. The device is intended to draw attention to the paths taken by bikes, highlighting these routes for motorists and other cyclists. When multiple bikes equipped with this device follow the same route, the effect is multiplied, creating a visual record of otherwise invisible traffic patterns.

Reactions to DIY projects such as these have been mixed. Government officials, perhaps understandably, tend to focus on liability issues and the cost of removing unsanctioned signs or lane markings. Reactions from cyclists have been more positive. Many bikers applaud the fact that something is finally being done to address the inadequacies of current bike route planning. Others worry about the safety issues that may arise from signage and lane markings designed by amateurs. Whether you approve or disapprove of this trend, it seems likely to continue as long as the pace of official bike infrastructure development lags behind the needs of cyclists. In my next installment: a look at what the future holds for bicycle infrastructure in Los Angeles.

Joseph Prichard is a Los Angeles-based designer, writer, and contrarian. His practice specializes in work for the nonprofit, arts, and public sectors. He will be speaking about Better Bikeways with GOOD contributor Alissa Walker at the Dwell on Design conference in L.A. in June.

From GOOD