Before there were cars, cyclists agitated for smooth, paved roads. In 1896 there was a massive protest in San Francisco with five thousand cyclists, demanding that roads be improved, with the motto “Where There Is a Wheel, There Is a Way.” The roads belonged to the bike.

And the bike changed the way people lived; in Hank Chapot's article "the Great Bicycle Protest of 1896" he concludes:

The bicycle remained an important option for workers and businesses for decades before being redefined as a toy following World War II. Its popularity rebounded in the 1930’s and again strongly in the 1990’s. In much of the world, it never left. Appearing between the horse and the automobile, the bicycle had helped define the Victorian era. It aided the liberation of workers (and especially women and children) as it changed concepts of personal freedom. On two wheels, individuals were free to move themselves across much longer distances at a greater speed than ever before, not dependent on horse or rail.

Now that the car is proving to be too expensive in terms of oil consumption, greenhouse gases and urban sprawl, (not to mention the cost of cars, parking and maintenance) bikes are coming back with a vengeance, and are now considered part of our urban infrastructure. So the big question is, should cyclists take their place in the road as they did 100 years ago, or be relegated to a separate, and often second-rate infrastructure?

First of all, as in the previous post where I stated that I wear a helmet, I will also state here that I plan my routes around the bike lane network in Toronto. But there are many different kinds of bike lanes, and some are safer than others.

For instance, many cycling activists are particularly derisive of the painted “door zone” bike paths, the most common variety where the bike lane is painted between parked cars and the traffic lanes. As the anti-lane activists point out, cars are free to travel at high speed, trapping the cyclist in a narrow strip where, if someone opens a car door without looking, there is nowhere to go. They suggest that cyclists are far better off in the traffic lane, where drivers must acknowledge their presence and either pass them safely or go at a slower speed. They might use as an example the recent death in Toronto of a 57 year old cyclist hit a car door and was bounced into the high speed traffic, where he was killed by a truck.

I personally have noticed that drivers speed by cyclists without a thought for them when there is a painted bike lane, but are a lot more careful in mixed traffic.

Toronto Bike Lane in Winter

In Winter, door zone bike lanes essentially disappear into the parking spaces, as cars are pushed out from the curb. Sometimes they just become a convenient place to store snow; they certainly cease to be part of the transportation infrastructure.

A new study in from the UK reported in the Guardian found that motorists actually drove closer to cyclists in a bike lane than they did when there wasn't one.

Ciaran Meyers, a postgraduate student at Leeds University's Institute for Transport Studies, hopped on his Marin Mill Valley hybrid with a camera mounted on it to measure passing distances. On a 50mph section of the A6, north of Preston in Lancashire, the readings found that motorists, on average, gave Ciaran an extra 18.1cm of space where there was no marked cycle lane compared to when there was. On a 40mph section of the same road the difference was 6.8cm, whereas on the 30mph section it was down to 3.7cm, seen as not statistically significant.

It appears that drivers tend to consider bike lanes as an extension of the driving lane and drift towards it. Another study by Wayne Pein in human transport concluded that bike lanes create their own dangers.

Bike Lane Accidents

Wayne Pein

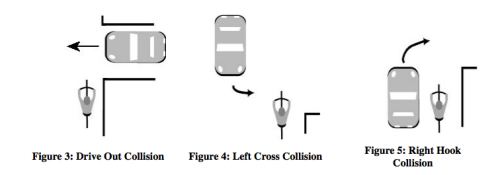

BLs give the illusion of safety, typically reported as bicyclist comfort, presumably due to a perceived protective effect from the stripe. Ironically, BLs exacerbate certain hazards for the unwary rider, the very rider they are installed to accommodate. BLs constrain bicyclists in the position where Drive Out, Left Cross, and Right Hook (Figures 3-5) collisions are more likely, the three main risks for otherwise legally riding bicyclists, and increase the hazard from debris (item 5). These crashes occur at driveway or roadway intersections, involve turning or crossing maneuvers, and are not prevented with BLs. Note: The Figures do not reflect BL striping.

Then there is the "ownership factor" that I mentioned above, that when there are bike lanes, the drivers of cars feel that they own the road, even though the law treats bikes as vehicles.

A BL sends the message to motorists and bicyclists alike that bicyclists have less right to be out of the BL. Where BLs exist, the remainder of the road becomes defacto Motor Vehicle Lanes. BLs create the expectation in motorists that bicyclists will and must stay "where they belong," in the BL. At the least, a bicyclist not in the BL is considered in an unexpected position.

On the other hand, when painted bike lanes are done right, they can be very effective. In lower Manhattan, the lane designers took a full lane away from auto traffic, creating a large buffer between parked cars and the bike lane, and a double line buffer between the drivers and the bike lane. I felt safer cycling there than I have just about anywhere else.

But the New York bike lanes demonstrate a political will that is rarely seen anywhere else in North America. Where I live, every meter of bike lane is considered a "war against the car", so the lane designs try to minimize the loss of parking spaces and driving lanes, and compromise their width and safety. But if you are going to put in a proper lane you need a physical separation, a dedicated space wide enough to accommodate passing, and proper signals. And if it is going to be really useful it has to be where people want to go, not some circuitous parkway.

They have been doing that in Holland forever; this quote is from a 1928 Modern Mechanix. But even in Holland and Denmark they are reconsidering. According to Wikipedia:

The Netherlands and Denmark, which have the highest rates of cycle usage combined with the best records for safety, used to give their segregated cycle path networks primary importance in achieving these goals. However, the largest study undertaken into the safety of Danish cycle facilities has found that safety has decreased as a result.[28] More recently, shared space redesigns of urban streets in those and other countries have achieved significant improvements in safety (as well as congestion and quality of life) by replacing segregated facilities with integrated space.

Our city employees at work, checking out the poutine

As I noted earlier, I use bike lanes, primarily because drivers are usually too busy eating lunch or talking on their cellphones to notice cyclists. But I believe that I have every right to be on any road in town as cars do, just as our city employees feel they have every right to park in the bike lane on their poutine runs. I suggest that we shouldn't meekly accept a little strip down the side of parked cars, but a properly designed, separated and maintained road of sufficient and equivalent quality and capacity. Otherwise, we are probably better off sharing the road.

From Planet Green