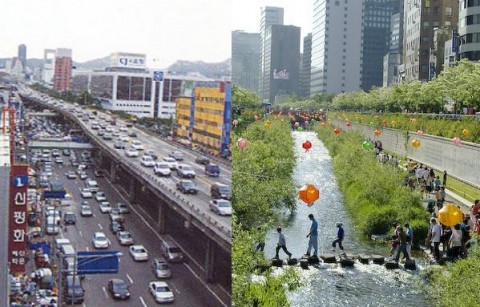

Seoul before and after

Remember a few years ago when millions of our fellow Americans started gorging on bacon and cheeseburgers in order to lose weight? The Atkins diet fad was an odd moment in our culture and probably one best politely forgotten. But one reason the scheme took off like it did is that human beings are innately fascinated by counter-intuitive effects. Most examples you hear about on teevee–”Rock-hard abs without getting off your couch!”–are malarkey, of course. But in certain charmed cases, it is possible to get thin by eating lard, so to speak.

One example is reducing traffic congestion by eliminating roads. Though our transportation planners still operate from the orthodoxy that the best way to untangle traffic is to build more roads, doing so actually proves counterproductive in some cases. There is even a mathematical theorem to explain why: “The Braess Paradox” (which sounds rather like a Robert Ludlum title) established that the addition of extra capacity to a road network often results in increased congestion and longer travel times. The reason has to do with the complex effects of individual drivers all trying to optimize their routes. The Braess paradox is not just an arcane bit of theory either – it plays frequently in real world situation.

Likewise, there is the phenomenon of induced demand – or the “if you build it, they will come” effect. In short, fancy new roads encourage people to drive more miles, as well as seeding new sprawl-style development that shifts new users onto them.

Of course, improving congestion is not the main reason why a city would want to knock down a poorly planned highway–the reasons for that are plentiful, and might include improving citizen health, restoring the local environment, and energizing the regional economy. More efficient traffic flow is just a wonderful side benefit.

Sound dubious? Here are several examples of how three cities (and their drivers) have fared better after highways that should never have been built in the first place were taken down.

CASE 1: Seoul, South Korea - Cheonggycheon highway

In 2002, Mayor Lee Myung Bak pledged to renew South Korea’s capital Seoul by eliminating a 1970s-era highway that literally represented a paving over of the Cheonggyecheon River. His radical plan replacing it not with another road, but with a restored stream along the old riverbed. The immediate result of the intervention was a beautiful new 1000-acre park in the center of the city, lower pollution, cooler temperatures city-wide. What wasn’t expected, however, was the city’s reduced traffic volumes. After all, the road carried 160,000 cars a day before it was closed. But the highway’s closing was enough to convince thousands of people to drive less, or change their habits, as the city offered better public transportation options.

Before:

After:

CASE 2: Portland, Oregon - Harbor Drive

The idea that it’s possible to remove a major road without creating traffic jams is not exactly a recent one: Portland proved its merits more than 30 years ago. Until the early 1970’s–a period when the city’s now-thriving downtown area was losing the battle with urban blight–there was a four-lane freeway known as Harbor Drive occupying the western shore of the Willamette River, creating a barrier between the downtown area and the waterfront. Even citizens and a few politicians began arguing in favor of taking down the road in the late ’60s though, Oregon’s Highway Department wanted to widen the thoroughfare.

Ultimately, the most important advocate for its demolition was then-governor Tom McCall. After a long and contentious political battle, McCall prevailed and the highway was closed in 1974. On the first day it was shut off to traffic, one of the highway engineers who predicted gridlock catastrophe reportedly called one of McCall’s lieutenants to congratulate him: there hadn’t been “a ripple” of disturbance in the city’s traffic flow.

By 1978, a greenway occupied the land where the Harbor Drive once stood. Twice expanded since then, the Tom McCall Waterfront Park is an integral part of Portland’s success in recreating itself as a 21st century city.

Before:

After:

CASE 3: San Francisco - Embarcadero Freeway

Arguably the US city where freeway removal has most improved urban life is San Francisco. The Embarcadero Freeway once stood elevated on the city’s waterfront. Two levels of concrete divided downtown from the bay. Though there had been a public push to demolish it since it was constructed, only after it was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake did the efforts crystallize, and it was never rebuilt. In its place today: a waterfront boulevard with bike trails, parks, and public exhibitions.

Before:

After:

CASE 4: San Francisco - Central Freeway

Also damaged in the Loma Prieta quake was the Central Freeway, which ran as a spur into the city. The thoroughfare was closed in 1992 and a few years ago rebuilt as a surface road named Octavia Boulevard. Though the boulevard is well-used, it’s no more congested than the far larger highway that it replaced, showing that traffic responds to the environment in which it is placed.

Before:

After:

Of course, this evidence doesn’t suggest that all road expansions are unnecessary, or that all highways should be removed. All of the highway demolitions cited above are in densely packed urban areas where other highways and reliable and convenient public transportation options are available. But the lesson is clear: If a major road is making a city a less livable and vital place that it would otherwise be, in many cases everyone benefits when politicians have the vision and guts to tear it down.

From The Infrastructurist